HDB – The bedrock of Singapore

Singapore has one of the world’s highest home ownership rates. The percentage of Singaporeans who were homeowners in 2021 was 88.9%, up from 87.9% the year before.

Despite having one of the most expensive housing markets in the world, with one of the most expensive penthouses found right here (Wallich Residence, USD $79.65mil), how has Singapore been able to achieve such high rates of home ownership?

To answer this, we would have to rewind a little to how it all started.

Since the 1920s, Singapore has been tackling with serious housing shortage. Matters worsened when there was an influx of refugees from regional unrest in the period of 1948-1960. After the ruling party was founded, HDB was set up in 1960 to tackle the housing crisis after its predecessor Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) failed to do so. Over the next 3 years, HDB was able to avert further housing catastrophe by building 31,317 flats to meet the demand.

Nonetheless, the government recognized that this was just a stop-gap measure. Times were uncertain. The nation was still young. There was severe unemployment. Most were living in slums. Homes were overcrowded with poor hygiene standards. Only 9% of the population then lived in public housing. Singapore was having a housing (and identity) crisis. The people desperately needed a sense of security.

Thus, the government launched the Home Ownership for the People Scheme in 1964 to assist the people in buying their flats. They now had a direct involvement in the prosperity of the nation through home ownership. In 1986, the government further incentivized home ownership by permitting the use of their Central Provident Fund(CPF) savings to service their mortgage and initial down payments.

With grants and assistance schemes launched over the years, it became increasingly attractive for the people to own high quality HDB apartments. Our housing system has become the bedrock for Singapore’s social structure and continues to be.

What started as an urgent solution to address the overcrowding and poor living conditions in early Singapore has evolved to become the epitome of public housing in the world and for the world.

Keeping HDB prices affordable

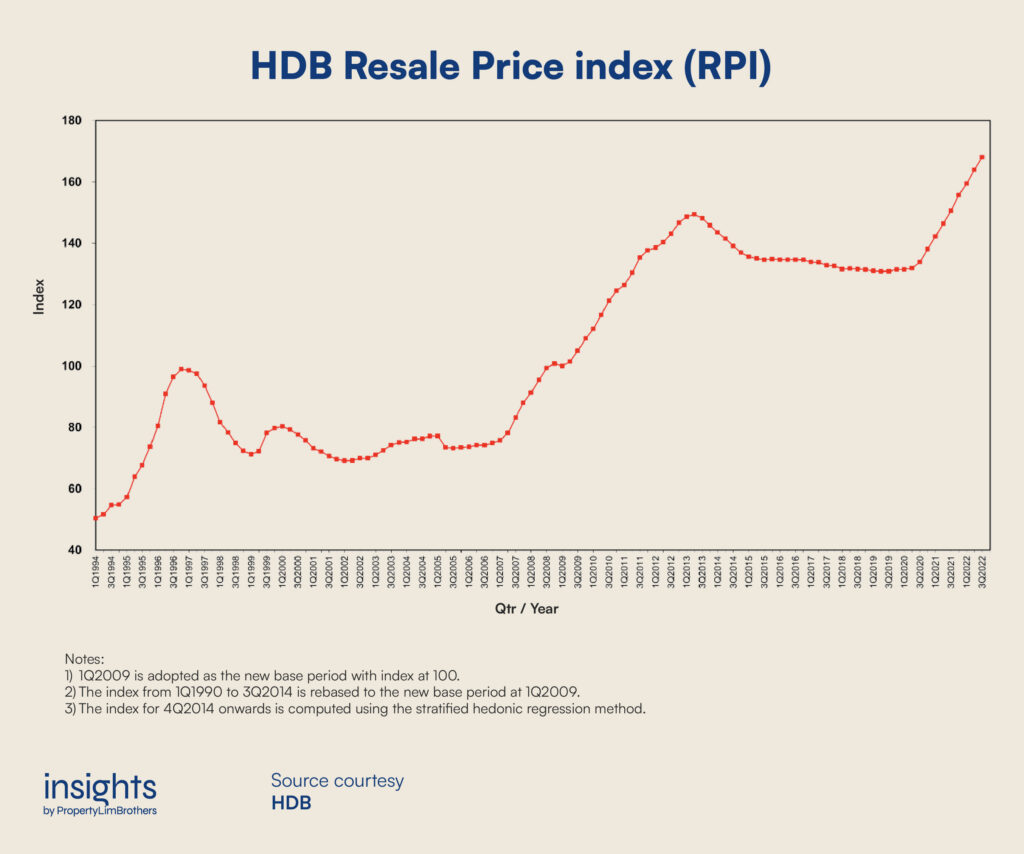

Over the years, HDB introduced several policies to keep HDB prices affordable and in tandem with income growth. These policies include placing a limit on the mortgage servicing ratio (MSR), the loan amount that one can borrow (Loan to Value ratio), tiered CPF grant amounts based on income etc. Needless to say, Singapore’s public housing market is closely regulated. Measures, such as the recent 30 Sept cooling measures that were meted out suddenly, they aim to bring the “bubbling red hot” HDB market down a few notches. Prior to 30 Sept, the HDB Resale Price Index (RPI) showed 10 consecutive quarters of growth. We were also seeing a record high number of million dollar HDB transactions, sufficiently causing the public to wonder whether public housing would become too expensive.

Nonetheless, Singapore, being a heavily trade-dependent country, is not immune to global and regional macroeconomic turbulence. For example, we were not spared from the recent US FED rate hikes that had led to a significant impact on Singapore’s internal interest rates.

Thus, how effective have our HDB policies been in “insulating” the HDB market from turbulent global events? To what extent were the policies able to keep public housing affordable and accessible in the midst of the uncertainty?

For the purpose of this article, let’s explore the effectiveness of the policies in place thus far to protect HDB market from high interest rate, high inflation and financial crisis in the past and what it means for homeowners moving forward.

How have HDB prices performed in previous macroeconomic turbulences?

The RPI monitors the market for public housing’s broad price change based on recorded resale transactions from various towns, flat types, and model types.

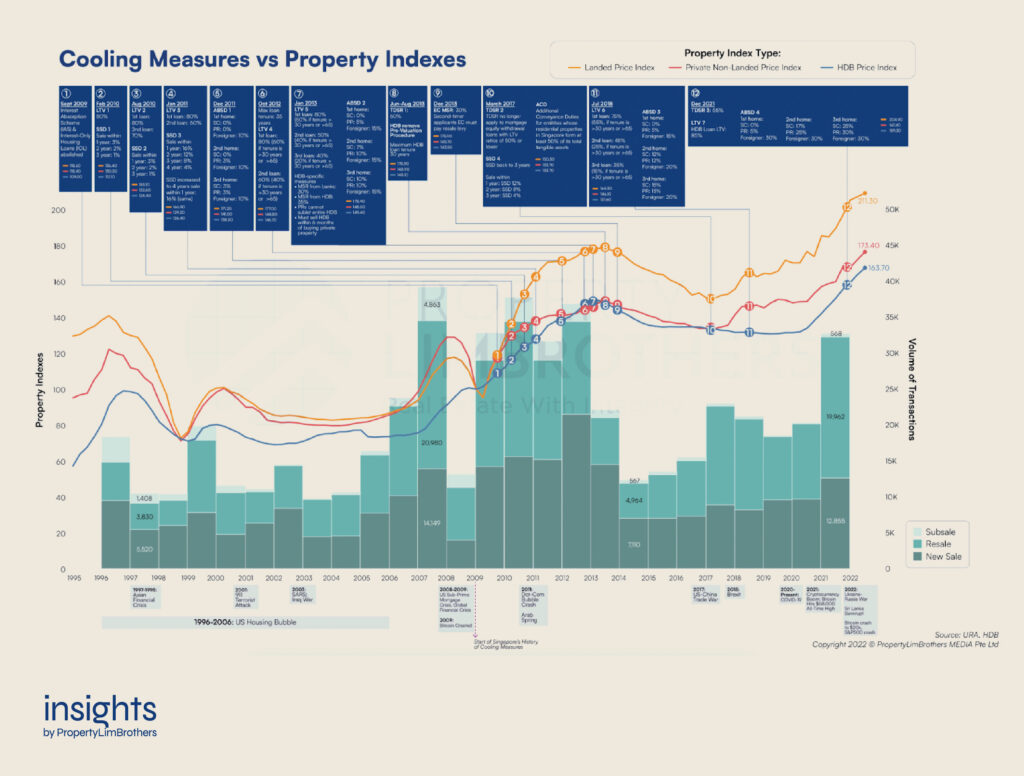

Before 1996, many were buying and flipping properties. In response to that, the government introduced the first cooling measure; imposing tax on earnings from real estate transactions. And not forgetting the Asian financial crisis that took place between 1997-1998, this proved to be a double whammy for the RPI, as shown by the sharp dip from 3Q1996 to 3Q1998.

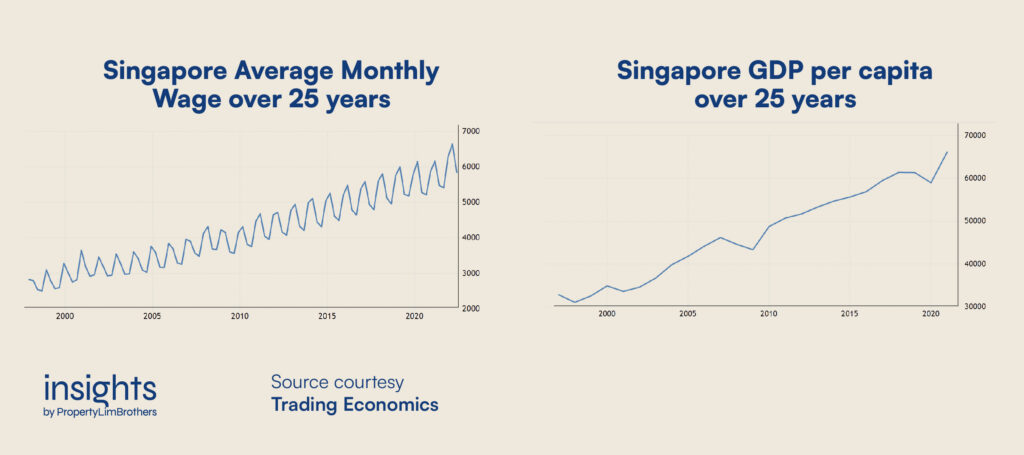

Since then, the RPI has shown an overall stable consistent growth with no sudden fluctuation, as observed in Figure 1. The new highs were higher than previous highs and the new lows were also higher than previous lows. The RPI trends in tandem with Singapore’s Wage and GDP per capita growth as shown in Figures 2 and 3. This is a strong indication that Singapore’s Housing market is moving in line with fundamentals and this is a good thing. This is because a housing bubble or market crash tends to occur when the housing prices start to move along with the whim and fancy of the public.

Now, let us take a look at the impact of macroeconomic events on the RPI. Firstly, let’s compare it with the previous high inflationary and interest rate environment back in 2007-2008, as shown in Figure 4 and 5. Generally, spending is reduced and buyers are more cautious in a high interest rate environment and yet, the RPI continued to trend upwards. This signifies a sustained genuine demand from buyers and prices made sense.

What about the impact of the past global financial crisis on the RPI?

These were the past events since 1997;

- 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis

- 1996-2006 US Housing bubble

- 2008 -2009 US subprime mortgage crisis, Global financial crisis

- 2011 Dot com bubble crash

- 2020-2022 Covid 19 Pandemic, S&P crashed

If we were to match these events against the RPI, it can be observed that apart from the impact of the Asian financial crisis in 1997-1998 and the first cooling measure introduced in 1996 that contributed to the sharp decline on the RPI from 3Q97-3Q98, the HDB prices were stable from 1999 onwards.

Moreover, the RPI continued to climb despite the US subprime mortgage crisis and global financial crisis in 2008-2009, Dot com bubble crash in 2011 and the recent Covid Pandemic in 2022.

These observations seem to suggest that the HDB market is well insulated from global events and corresponds in tandem with the growth of the nation in terms of GDP and income growth which correlates to spending power. Was it pure coincidence? Perhaps multiple strokes of luck?

Let’s dive a little deeper into the policies that were put in place since 1996 that could have contributed to this “protective cloak” that has insulated the HDB market from the instability of global markers.

How has government intervention helped to insulate the HDB market?

One of HDB’s missions is to ensure price stability in the public housing market. To achieve that, the interaction between the supply and demand factors must be carefully managed. Any imbalance left unchecked leads to undesirable outcomes. For example, the people in Sweden are witnessing a huge decline in the demand for homes as buyers are already overly leveraged at 200 per cent of the income of each household. This research conducted by Bloomberg also shows the list of countries that are most likely to face a price correction as their housing prices no longer move in tandem with the fundamentals.

We’ve seen earlier from the charts that HDB prices are generally stable. How has HDB been able to pull off such a feat not just once, twice but consistently? For this, we will need to take a deep dive into some of the HDB policies, understand the rationale of their existence and how they were introduced to balance the scales of supply and demand consistently.

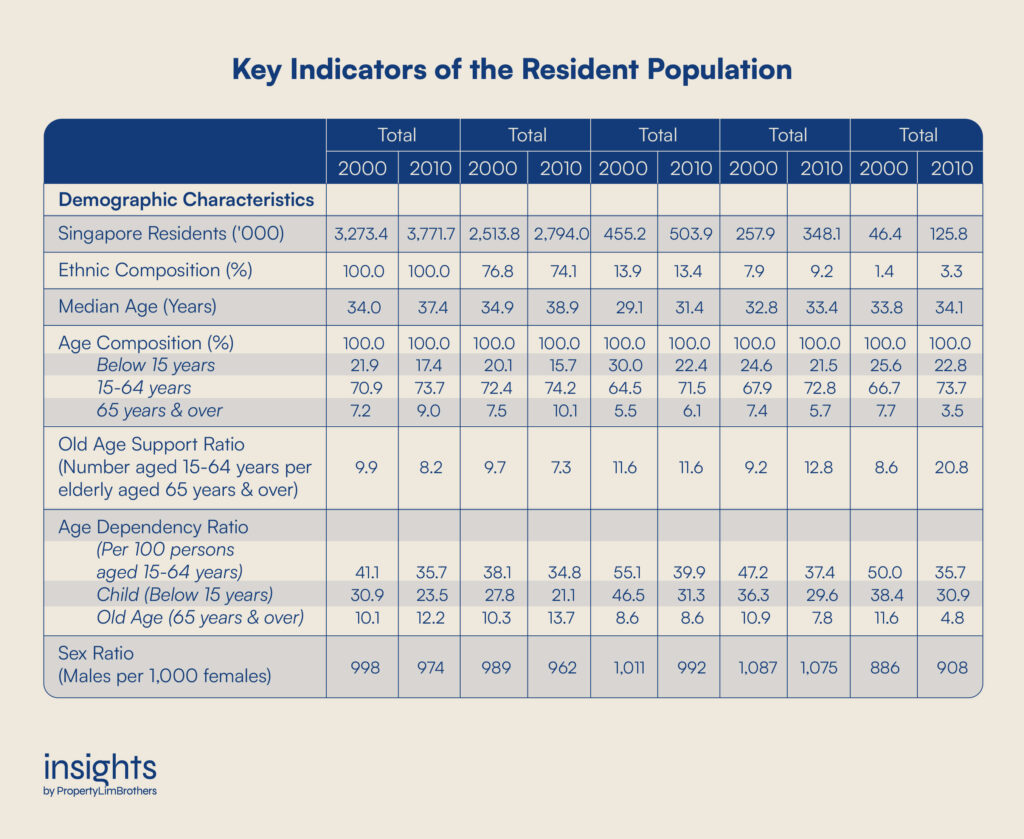

Firstly, let us journey back in time to the year 2010. Back then, according to Singstat, 73.7% of the total population was between the ages of 15-64 years of age. This meant that the majority of Singapore’s population would be at the stage of either starting a family or expanding their family in the next 10 – 15 years. A surge in demand for homes was expected in the coming years. Unless the supply of new homes ramp up to match the impending demand, resale homes would become such a rare commodity that the prices could potentially become unreasonably high.

The governing bodies must have been cognizant because from 2010 onwards, as seen in the figures below, they started to increase land supply. There was a sharp increase in the plots of land released for residential purposes as compared to previous years. This was especially so in the OCR region, where most mature estates such as Ang Mo Kio, Bedok, Clementi, Pasir Ris, Serangoon and Tampines are at. With the majority of Singapore’s population staying in mature estates, the demand for such estates was expected to be higher as those who are looking to buy their new home would generally prefer to stay near to family members for convenience, familiarity and proximity grants.

However, the land released in 2010 meant it would take another 3 to 4 years for new homes to be TOP ready. As demand started to build up between 2010-2013 before the new homes were ready, both the private and HDB resale prices started to climb, as seen in Figure 1 above. Once again, the governing bodies were on the ball. The cooling measures introduced by MAS in 2013 effectively eased the fervour. Coupled with the oversupply of TOP ready new homes from 2014 onwards, the HDB resale prices consolidated for the next few years. The scales were balanced once again.

Now, let us consider a more recent event; Pandemic-led soaring home prices from 2020 to 2021. The construction sector which came to a halt for the past two years is only beginning to recover. Interest rates were low and there was liquidity in the market to encourage spending. This led to the unquenchable demand for products such as real estate. However, the construction and manufacturing sectors were just not able to meet the demand. Low supply in a high demand environment led to an inflationary environment with rising resale HDB prices for nine consecutive quarters.

The scales were quickly tipping.

To address this, the governing bodies had to reduce demand while increasing the supply.

The former was tackled by introducing further cooling measures in order to maintain housing affordability and encourage prudent spending. From 16 December 2021 onwards, homeowners taking a HDB loan could only borrow up to 85%, as compared to 90% previously for both new and resale flat applications. In addition, ABSD rates were also increased for homeowners purchasing their second, third and subsequent properties.

This proved to have little impact on reducing demand as HDB resale prices continued to climb. Thus, another round of cooling measures was introduced on 30 September 2022 to further lessen the demand. Maximum loan amounts permitted for mortgages were now reduced and a 15-month wait-out time will be imposed before allowing current and past owners of private homes to purchase non-subsidized HDB resale apartments.

At the same time, governing bodies started to signal moves to increase the supply of public housing. In comparison to the BTO sales exercise in August 2022, there are 94.3% more BTO flats available in the November 2022 BTO. Furthermore, in the upcoming February and May 2023 BTO sales exercises, HDB also plans to release between 8,200 and 9,200 apartments. It is also noteworthy that new apartments are not priced by HDB to cover the cost of the land and building. Instead, it uses generous subsidies to significantly underprice apartments so that Singaporeans may afford them. In the recent news released on 8 December 2022, it was also announced that 7 more plots of land would be released in the first half of 2023 for private residential purposes under the Government Land Sales(GLS) programme to further bump up the supply in the pipeline.

The latest cooling measures, coupled with news of more homes in the pipeline, seem to have proved effective as fewer homes exchanged hands in October 2022, the first downtrend in 8 months. Nonetheless, the volume of transactions picked up slightly in November 2022 as sellers became more realistic with their asking prices as the recent cooling measures had reduced the pool of potential buyers significantly. Coupled with the rising interest rates into 2023, we do expect a continued decline in the volume of transactions.

The scales are rebalancing again.

How is the private residential market regulated differently from the public housing market?

What about the private residential market, which is owned by 20% of Singapore’s population?

Take for example the Asian Financial crisis that was generated by overly hopeful sentiments in the late 1990s generated by the anticipation of future growth in Asia instead of true economic fundamentals. This led to consumers belittling risks, rampant over-borrowing and lending and overly inflated private property prices. To “flush out” speculators, the government intervened unexpectedly in May 1996 . These measures included reducing borrowing limits for both local and foreign buyers, taxing property gains as income and ramping up the supply of private residential homes. These well-timed measures were effective in reining in the runaway prices, though Singapore was not spared from the impact of severe correction throughout Asia when the fundamentals could not keep pace with the price.

MND minister Desmond Lee reiterated that private housing prices must move in tandem with the economic foundations. And just like the measures introduced in May 1996, governing bodies will continue to adjust policies when needed to prevent investors from acting in a similar speculative manner to keep the private housing market stable and sustainable in the land-scarce Singapore.

Takeaway

It is evident by now the government’s emphasis on a stable housing market. Singapore is proactive in keeping housing prices in check, especially in the HDB market. We can safely conclude that Singapore’s HDB market is largely insulated from macroeconomic turbulence by design. For example, HDB decides who can buy the flat, when the flat can be sold and the types of grants one is eligible for. HDB also determines the valuation of the flat and makes it known to buyers only. The heavily regulated HDB market ensures that everyone can afford public housing if they choose to. This also means that one should not see their HDB as an investment tool.